A transcendent golfer occupies our head space like no other athlete, thanks to the unadorned intimacy and longevity afforded by the sport. We stand mere feet away from them on the tee box. We grow old with them. We play their game, or a lesser, mortal version of it, squeezing in 18 holes on Sunday mornings before settling in for the great champion’s final round.

Woods is now in his fourth decade in that role. Now that teenaged phenom, later a twentysomething world-conqueror and thirtysomething cautionary tale, is a 45-year-old hospital patient in Los Angeles whose ability to play competitive golf again, in the aftermath of Tuesday’s accident, is far down on the list of pressing concerns: walking again, running with his kids, leading a “normal” life.

AD

The impulse to wish Woods a speedy and full recovery comes from the purest of places. The impulse to wish him a return to golf, on the other hand, sometimes feels as if it’s less about Woods’s happiness – though we can assume it is something he wants – than our own.

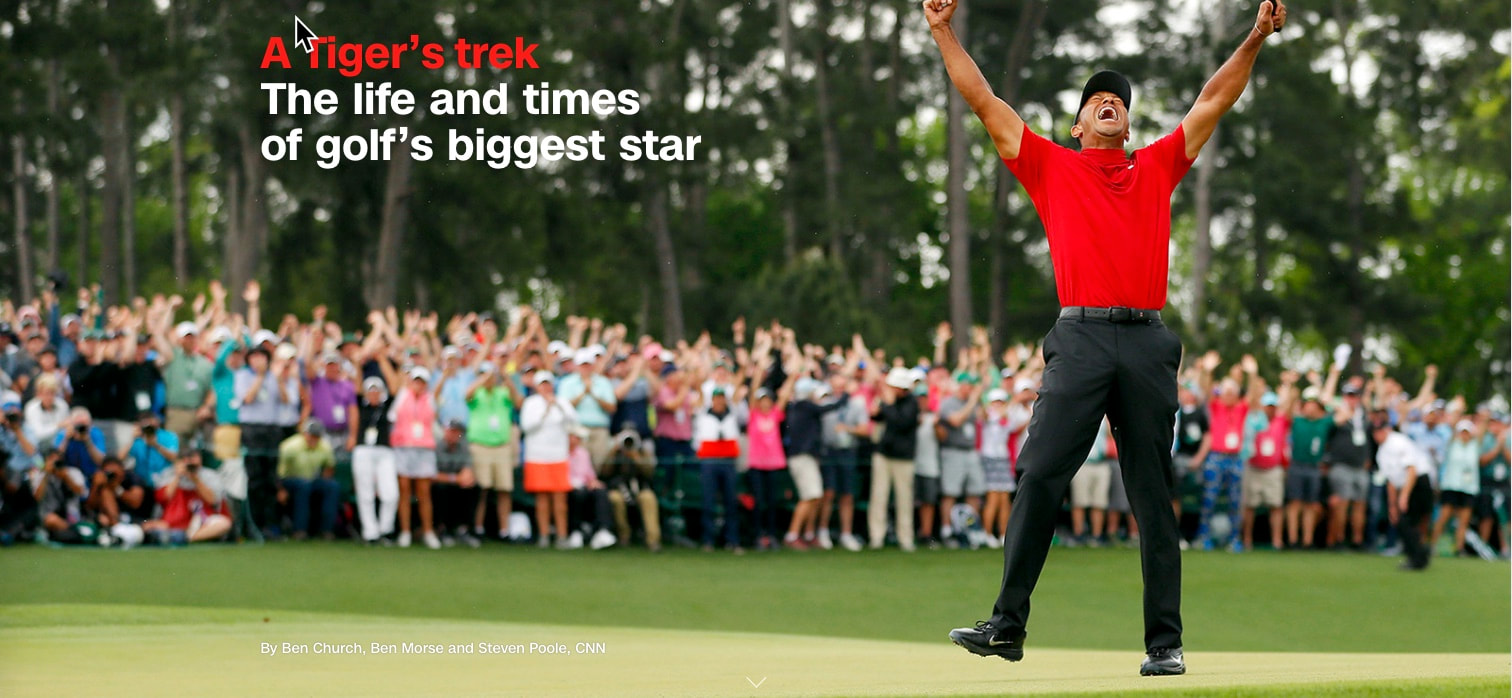

After the comeback win at Augusta in 2019 – which itself followed a decade in the wilderness of inconsistent golf, countless back and knee injuries and an image-destroying personal crack-up — we came to believe we might be able to enjoy a few more years of Woods as a major-championship contender, followed by another decade or two of nostalgic presence and occasional relevance.

Such is the nature of golf.

Tiger Woods’s genius has never been a free gift. Now his only task is to heal.

Woods still has a year to go before he reaches Jack Nicklaus’s age when Nicklaus won the 1986 Masters, 14 years until he is the same age as Tom Watson when Watson darn-near won the British Open in 2009. Arnold Palmer teed it up in The Masters – as a competitor, not a ceremonial first-tee figure – until he was 75. Yeah, he missed the cut. But the size of his galleries was a testament to the hold a transcendent golfer retains over the sport deep into their golden years.

AD

Woods had a chance to be that guy, as long as his body and his impulses didn’t betray him. We have watched him grow from being someone’s son to someone’s husband to someone’s father – he was better at some of those roles than others – and could easily imagine him as someone’s grandfather.

By making it this far, still his sport’s biggest draw nearly a quarter-century into his professional career, Woods has already redefined what it means to be a superstar for a wide swath of the public. He may have been a once-in-a-generation talent, but his impact cut across several generations — yours, your parents’ and maybe your kids'.

Much of what we have come to know about the nature of modern superstardom in sports we learned first through Woods. His backstory had race as a central element – from his mixed-race lineage to his tortured self-description as “Cablinasian” to his historic win at Augusta National – long before it became an essential part of sports-page discourse.

Tiger Woods walks to the 15th green during practice for the Masters golf tournament at Augusta National Golf Club, Tuesday, April 3, 2018, in Augusta, Ga. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

His career has encompassed the transformation of athletes into brand ambassadors, the rise of social media as a marketing force and the explosion of television money across sports. In 1997, Woods’s first year as a professional, the purse at the U.S. Open was $2.6 million. In 2020, it was $12.5 million. Nicklaus took home $5.7 million in career PGA Tour earnings. Woods is currently at $120.9 million.

Woods also, of course, gave us perhaps the most vivid example of the downside of fame. The cute videos of two-year-old Tiger showing off his swing on the Merv Griffin Show. Those weird quotes from his father, Earl, that Tiger would be “bigger than Gandhi.” When Tiger was a young superstar, it could all be interpreted as evidence of his manifest destiny. But as Tiger’s life fell apart, it came to be viewed as the caustic residue of the undue pressure a father had placed on his son.

There still has not been a more public or more sordid downfall for a superstar athlete than the one put into motion on Nov. 27, 2009, when Woods backed his Cadillac Escalade down his driveway in Orlando, and into a fire hydrant and a tree. Three months later, his 13 ½-minute apology for all his numerous affairs was carried not only by ESPN, but by the major television networks and cable news channels.

Everything he ever did was big and bold and made-for-television: the longest drives, the most wins, the highest earnings, the largest galleries, the swooshiest outfits, the toothiest smile, the fiercest fist-pumps – and later, the grandest and most spectacular implosion, and the most unforgettable comeback.

Woods’s professional life, to this point, can be divided into three tidy chapters: the 12-year span between 1997 and 2008 when he won 14 majors and redefined the outer limits of golf and sports stardom; the lost years of 2009 to roughly 2017; and the renaissance that began in 2018, culminating with the catharsis of the 2019 Masters victory.

PGA world reacts with messages of concern, support for Tiger Woods

If he seemed in the first phase like a cyborg programmed to conquer his sport, and in the second phase like a pitiable shell of a man, the glory of phase three was in the discovery he was neither of those things – just a guy trying to raise his kids and be a better man. The triumph of Tiger was in reigniting his professional life by fixing his personal life – in admitting he had to change, which is easy, and then actually doing it, which is not.

He once fascinated us because he could do things no one else on the planet could do with a golf club. The human eye is drawn to mastery, and Woods, for a long while, was better at golf than anyone else was at anything. Now, he fascinates us because we have come to understand he is exactly like us, faults and all. And because like us, on his best days he could still bring it.

Woods was both most relatable and most likeable in this third phase, and the hope was that this renaissance would continue for a good, long while – that he might still be a regular force at the majors for a few more years, maybe even equal Nicklaus’s record of 18 major titles. His latest back surgery, in January, punctured that hope. This week’s gruesome accident exploded it.

When his bones heal and his psyche allows a return to public life, he will most likely enter a fourth phase, the nature of which is still to be defined. Whatever that ends up looking like for Woods – from launching another improbable comeback to resigning himself to a ceremonial role – we have no choice but to accept it. We’ve had to readjust our expectations for him before, and now we have to again.

But if this is the end of Woods as a competitive force in his sport, we can permit ourselves a few moments of wistfulness for what was lost. For as much as he’s given us, we always counted on a lot more. For as long as we’ve been captivated by Tiger Woods, and it’s going on a good quarter-century now, we still weren’t ready to say goodbye.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed